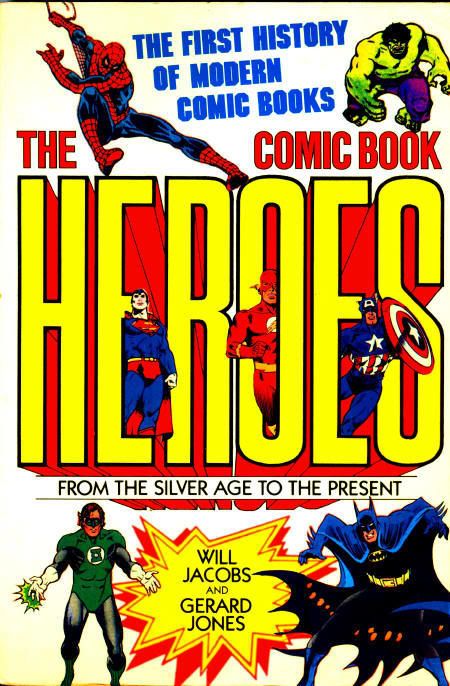

Sorry for a post title whose length reminds people of that Fiona Apple album, but it's what appears on the cover to both editions of the book I'll be discussing off and on for the next several months. Also, it helps differentiate from "The Great Comic Book Heroes" by Jules Feiffer, which I'll also be returning to soon.

Will Jacobs' and Gerard Jones' non-Great "Comic Book Heroes" was first published in 1985 by Crown Publishers Inc. Don't take the lack of greatness as a criticism, as I've never read the book. I bought my copy at the San Diego Comic Con in 2000, and sat on it for eight years. I did this because I'd already purchased the 1997 Prima Publishing edition when it came out, and it had turned out to be the best book on comics I've read before or since. The latter edition was greatly expanded and updated by Jones alone, with enough of the original cannibalised to warrant a secondary credit to Jacobs. I decided it was about time to compare the two, so I'm reading both editions simultaneously. That's why this isn't a review, as I expect I'd rather just chart my progress with commentary.

To begin with, Heroes '85 is clearly the creation of two major DC Silver Age fanboys, while the latter is by a jaded industry veteran still better over his recent departure from the industry. The beauty of '97 is the candor and clarity of the work, as Jones rightly expects to be done with scripting comics. With his experiences still fresh in his memory, Jones balanced careful research with hip-shooting and a bit of backroom tales. '85 feels more like a lengthy article for "Amazing Heroes," as it lacks the bite, color, and depth to rate "The Comics Journal." It's still fine historical reference, but focuses more on the now oft-tread recollections of the comics themselves, rather than the efforts and inspirations behind their creation. For that, go directly to '97.

In Chapter One of both editions, the scene is set regarding the mediocrity of the DC Trinity and post-Code comics in general. Superman stories were modeled after the TV show, pitting "the first and greatest of heroes against an unending stream of petty crooks full of tiresome schemes and armed with kryptonite." Batman was disappointing with "lackluster stories and coarse drawings." Two variations of a line regarding the Amazing Amazon are brutal:

"The third survivor, Wonder Woman, also a DC property, had lost both the original writer and the original artist who had made her so idiosyncratic and so interesting in her first ten years; their successors were unable to make her either."

"And there was Wonder Woman, whose adventures weren't just dull, but usually didn't make sense.

'97 then flashed back to the early days of comics, where DC began with "pulp writer and master liar" Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson, too cash poor to buy newspaper reprints, so he conned hungry youths to draw new strips and "vanished into the night when they came for their pay." Not likely to catch that kind of straight talk in one of the many official DC histories, and Jones continued to hint at the blood shed by mafia ties that would be later explored in detail with his "Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters, and the Birth of the Comic Book." Jones then moved to the Wertham crusade's impact: "There had been nearly 650 comic book titles in 1952; by 1956 there were barely 400, and a few years later there would be scarcely 250." Of the eventual Marvel Comics publisher, Jones noted, "Martin Goodman's tower of schlock was collapsing faster than Babel." Those types of sordid details were missing in '85, which was more interested in tall tales from Mort Weisinger and how great Carmine Infantino was on the Flash relaunch.

Speaking of which, Jacobs and Jones detailed friends Weisinger and Julie Schwartz path through the pulps into comics, where they ended up working together. Of Flash writer John Broome, Jones and Jacobs opined that he "took the stuff of superheroes, the crude violence... and made it something consciously modern, self-amused, and expertly fun... Broome had a wry sensitivity to the little strokes of humanity that gave substance to even his most absurd creations." The difference was in '97, Jones could confide that he was also "a gentle young writer woth an intellectual bent, drawn to Asian art and travel... avoided the DC offices, preferring his house upstate where... he grew copious quantities of the forbidden vegetation that made so many jazzbos hear a little deeper and play a little lighter." Likewise, the matured Jones could link the sucess of the Flash revival with the "unprecedented political calm and social satisfaction" of the 1950's. "If you were young enough, it was almost possible to believe in a world where order and neatness were fundamental, where villainy was the work of amusing goofballs..."

'85's second chapter, "Strange Adventures in Space," was largely unaltered in '97, aside from switching places with its follow-up, "The Superman Mythos." Both were interesting and informative regarding the influence of science fiction on new features and in reinvigorating the Man of Steel. Taking advantage of C.C. Beck to essentially recreate the Marvel Family in Kryptonian garn didn't hurt. In '85, the authorial pair considered, "Weisinger had discovered that Superman grew more heroic as he grew less powerful." However, it took Jones twelve years to insightfully expound on the arrival of Kandor and Kal-El's many returns to doomed Krypton. "This introduction of pathos to Superman, the realization that not even all his powers could give him back what he loved most in life, elevated him from mere costumed crime fighter to something close to a tragic figure. This was a dark element alien to Julius Schwartz's aesthetic, an almost Greek sense of fatalism... fate presented almost as a physical law... there is also a profoundly Jewish sense to Superman's tragedy, planted there since Siegel's origin story with its references to Moses, amplified in the hero's obsessive returns to the holocaust of his home world now that Weisinger was giving his heart to the hero."

The 1985 edition measures 6"x9" at 292 pages, while 1997 offered 8 1/2" x 11" and 400 pages, the former's appearing at roughly actual size above (at least on my 14" monitor.) If anything, the text size and spacing shrank over the years, so you do the math. I'll return to this comparison soon...

You can buy the 1997 edition of The Comic Book Heroes: The First History of Modern Comic Books - From the Silver Age to the Present from Amazon.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment